A group of researchers, led by Harrisburg University of Science and Technology Professor Dr. Steven Jasinski, have recently published a study on fossil carnivoran mammals from Pakistan and India.

Jasinski, of HU’s Department of Environmental Science and Sustainability, and researchers from the University of Sialkot, the University of the Punjab, and the University of Okara described new fossil specimens of carnivoran mammals that lived in southern Asia from around 15 to 2.5 million years ago.

These new specimens add important new information to our knowledge of these carnivorous mammals, according to the new study published in the scientific journal Historical Biology. The research was published by Jasinski, along with fellow researchers Sayyed Ghyour Abbas of the University of Sialkot, Khalid Mahmood and Muhammad Akbar Khan of the University of the Punjab, and Muhammad Adeeb Babar of the University of Okara.

The Siwaliks, also called the Siwalik Group, is a set of terrain or mountainous region and part of the outer Himalayas. The Siwaliks stretch through Pakistan, India, Nepal, and Bhutan. The fossil animals lived in the shadow of the Himalayan Mountains from around 18 million years ago to about 1 million years ago. These fossil deposits are known to have a diverse mammal fauna, with many species of artiodactyls (such as bovids, suids, hippopotamuses, and giraffoids), perissodactyls (such as rhinoceroses and horses), proboscideans, rodents, primates, and carnivorans. This latter group, including carnivorous mammals like hyenas and cats, was the focus of the study by Jasinski and his co-authors.

While some of this fossil material was collected as far back as 1969, much of this material has been collected as isolated fossils over the last several years. As is often the case with fossil mammals, fossil teeth provide some of the best material to identify, and most of these are fossil teeth, with some specimens representing partial lower jaws.

Newly described fossils include material referred to amphicyonids, barbourofelines, felids, viverrids, herpestids, and hyaenids. Amphicyonids, commonly called bear dogs, were a group of carnivorous mammals, distinct from bears and dogs, that went extinct around the end of the Miocene period just over 5 million years ago. Barbourofelines, an extinct group of cat-like carnivorans sometimes called false saber-toothed cats, often had enlarged canine teeth and went extinct late in the Miocene just before 7 million years ago. Felids, otherwise known as cats, are represented by several different types including primitive types and the often saber-toothed machairodontines.

Viverrids are small- to medium-sized carnivorans that currently live in Africa, southern Asia and southern Europe. They are largely made up of the commonly called civets and genets. Herpestids are another group of small- to medium-sized carnivorans that currently live in Africa and southern Asia. They are largely made up of the mongooses and the photogenic meerkat. Hyaenids, commonly known for their ability to crush and consume bones and the laughter-like sounds they can make, are highly diverse in the fossil record. They are represented my multiple types including the more dog-like or jackal-like ictitheres and more modern, robust members.

Some of these recent discoveries, along with renewed effort by researchers to look back at specimens already collected and those in museum collections, are providing us important new information. “Putting energy into not only getting into the field to find and collect new fossils, but also investigating or reinvestigating specimens already in museum collections is providing us vital new information in understanding not only what life was like millions of years ago, but also providing key data to how these carnivorans were evolving and changing through time” said Dr. Steven Jasinski.

These new specimens are not only adding further support to some of the previous information scientists have found about this region in the past, but also provide new evidence and add to the biodiversity of this region.

Among the fossils reported, Jasinski and his research group describe the first herpestid fossils from the Chinji Formation, including teeth and lower jaw material. They also report the first hyaenid fossil material from the Tatrot Formation and the first jackal-like hyaenid (ictitheres) from the Dhok Pathan Formation.

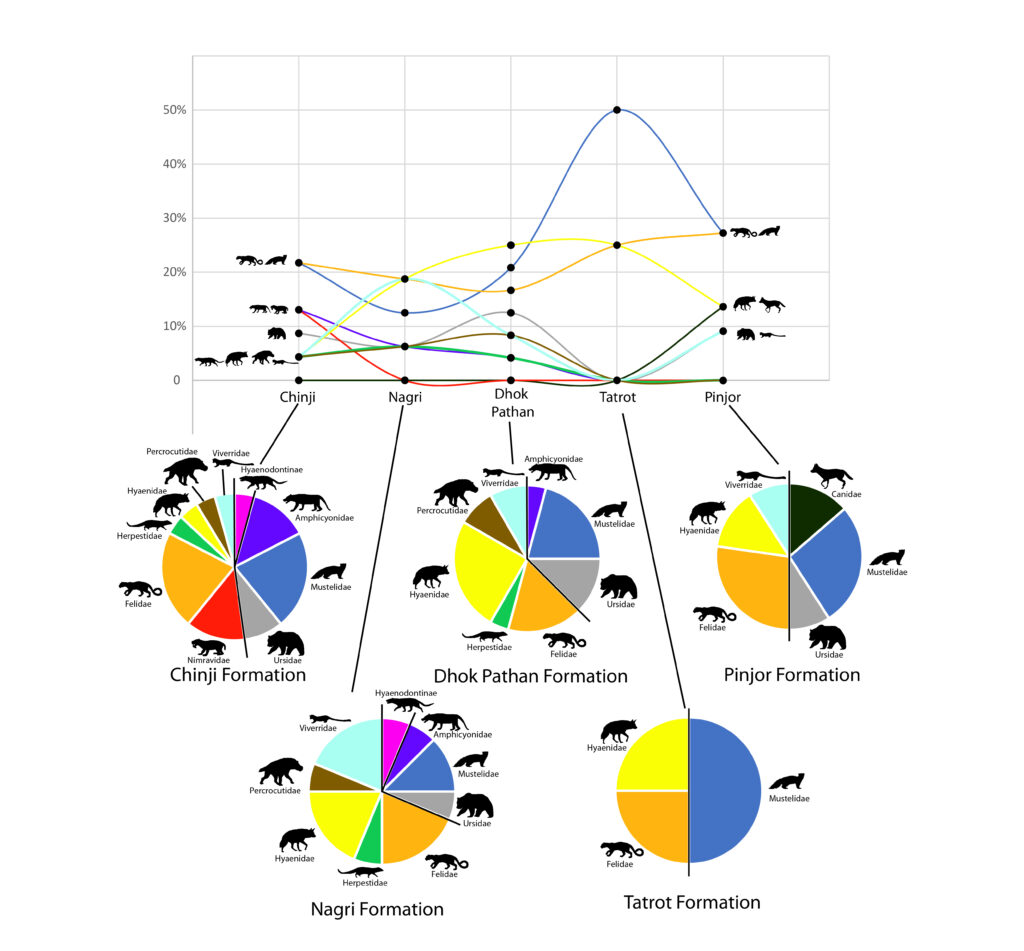

In addition to these new occurrences and this updated data on the palaeo-biodiversity of this southern Asian region over the least several million years, the authors also sought to identify trends in the carnivoran fauna during this time period representing around 10 million years.

Moving through time, several carnivoran groups disappear from the Siwaliks, either through extinction or through extirpation. Among these are barbourofelines, followed by amphicyonids and percrocutids. Felids and mustelids remain the most diverse through time, while canids are late arriving carnivores.

“These fossils help provide us a more complete picture of life in this region during this time period, namely from the middle Miocene into the Pliocene” said Dr. Jasinski. “We see a diverse ecosystem changing in the shadow of the Himalayas as these mountains continue to grow.”

This is a time of distinct changes both in the uplift of land in this region, but also general climate changes. Global temperatures were generally cooling throughout this time, and mammalian carnivores were dealing with these changing conditions just as other living animals and plants were.

“As we continue to gather more fossils and information, we continue to gather data that helps provide us a window into life in the past, but using the fossil record we can also see how life changes through time,” said Dr. Jasinski. “If we use what we know about the past, we can make predictions about the future. Some of the most at risk large animals in the world today are carnivorans such as polar bears and tigers. If we study the past, we may be able to make better hypotheses about what will happen to them due to the current changes in the climate.”

The research team hopes to continue to find more fossils and paint a clearer picture of this key time in the past. Using the fossil record to understand changes through time is one of the ways scientists attempt to predict the future. “If we can understand what may happen moving forward, we may have a better idea as to what to do to avoid particular aspects of those forecasts,” says Dr. Jasinski, “and if it can help us understand the potential future of at risk species, including these charismatic carnivores, we may still have hope they will be around for generations to come.”

To read the team’s paper on fossil carnivores from southern Asia, visit this link or you may email Dr. Jasinski and ask for a PDF version: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/08912963.2022.2138376?journalCode=ghbi20.

Jasinski has also been the member of other research teams that have recently named multiple horned dinosaurs from New Mexico. He and researchers from the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, the University of Pennsylvania, and the University of Bath named the new dinosaur species, including Menefeeceratops sealeyi, further discussed here, Sierraceratops turneri, further discussed here, and most recently Bisticeratops froeseorum, further discussed here.

ABOUT HARRISBURG UNIVERSITY

Accredited by the Middle States Commission on Higher Education, Harrisburg University is a private nonprofit university offering bachelor and graduate degree programs in science, technology, and math fields. For more information on the University’s affordable demand-driven undergraduate and graduate programs, call 717-901-5146 or email, Connect@HarrisburgU.edu. Follow on Twitter (@HarrisburgU) and Facebook (Facebook.com/HarrisburgU).